I work at the intersection of optics, materials science, and sustainability, developing advanced optical and photoactive materials for a net‑zero future. This has led me to spearhead four distinct research projects:

- Turning sunlight into clean fuel. I am pioneering luminescent solar microreactors that convert the full solar spectrum into useable energy, enabling efficient, off‑grid production of sustainable fuels and chemicals.

- Archival storage, reinvented in glass. I explored a wide range of glass materials designed to preserve data for centuries with zero degradation.

- Powering the IoT with the light around us. I developed next‑generation luminescent coatings that help recycle diffuse indoor light to power small devices.

- Photochemistry at the smallest scales. Through fibre‑based spectroscopy using hollow-core fibre microreactors, I investigated the kinetic and mechanistic behaviour of next‑generation photocatalysts.

Turning sunlight into clean fuel

I am currently leading a project on luminescent solar microreactors (LSMRs) as part of an EPSRC Research Fellowship based at the University of Cambridge. These devices absorb solar photons and convert them to more suitable wavelengths for photocatalysts, leading to a significant increase in solar-to-chemical efficiency.

The Challenge

Climate change and the global transition to net‑zero is one of the defining challenges of our time. While renewable electricity from solar and wind has grown rapidly, many sectors such as long‑haul transport, steelmaking, and chemical manufacturing cannot be easily electrified.

Low‑emission hydrogen offers a promising alternative, but today almost all hydrogen is still produced from fossil fuels. Clean hydrogen can be generated through water electrolysis, yet deploying electrolysers at scale would place enormous additional demand on national power grids. To fully decarbonise our energy system, we need new off‑grid, decentralised ways to produce clean fuels.

One promising pathway is the direct conversion of sunlight into chemical energy, so‑called solar fuels, using photocatalysis. The challenge is that conventional photocatalysts cannot efficiently use the full solar spectrum. Near‑infrared (NIR) light is too low in energy to be absorbed, while high‑energy ultraviolet (UV) light can damage the catalyst. This limitation can be overcome by converting the incoming sunlight. Upconversion combines two low‑energy NIR photons into a single higher‑energy photon that the photocatalyst can use. Downshifting converts damaging UV photons into lower‑energy light that avoids catalyst degradation.

More details on my fellowship project are available on the UKRI website.

Archival storage, reinvented in glass

As part of a Cambridge Residency at Microsoft Research (Sep 2024 - Dec 2025), I investigated new optical materials for Project Silica, an archival data storage technology, based on writing data into glass with femtosecond lasers. A video summary of the project is available here.

The Challenge

Humanity still lacks a truly sustainable, cost‑effective way to preserve data for the long term. Traditional magnetic media degrade, require constant monitoring, and must be replaced every few years, driving up energy use, emissions, and cost.

Glass storage changes the equation. It’s low‑cost, ultra‑durable, and naturally resistant to heat, humidity, particulates, and electromagnetic fields. As a WORM medium, it provides built‑in immutability and an air‑gap‑like security model. It also offers fast access without mechanical spooling. With a lifetime measured in centuries, glass eliminates data migration, scrubbing, and media refresh cycles. And because it enables true operational proportionality, the cost of storage scales only with how often data is accessed, not how long it’s kept.

Associated publications coming soon …

Powering the IoT with the light around us

As part of my first postdoctoral role (Sep 2021 - Aug 2024), I led on a collaborative scientific project between the University of Cambridge and McMaster University (Canada). I designed an optical setup to fabricate luminescent patterned films (or luminescent waveguide-encoded lattices - LWELs) for light harvesting. These patterned films are based on acrylate and epoxide polymers and can be applied to the surface of photovoltaic cells to boost efficiency. This work has resulted in the filing of a patent WO/2024/252003.

The Challenge

The Internet-of-Things (IoT), a network of sensors and actuators connected to computing systems, holds great commercial and societal potential, from streamlining operations to enhancing human health. Many of these will be “fit and forget” devices, creating an urgent demand for off-grid power sources. Currently, most IoT nodes are powered by batteries. However, battery replacement translates into incremental costs through the product life cycle, huge environmental impact during disposal, and significant safety risks in some applications. Could we recyle ambient indoor light to perpetually power these devices instead?

LWELs are advanced polymer materials designed to boost the performance of solar cells under diffuse indoor light. The LWEL is retrofitted to the surface of a solar cell where it increases the angular collection of diffuse light and converts indoor light via photoluminescence to better match the spectral response of the underlying solar cell. LWELs are therefore designed to boost the power output of solar cells, such they have sufficient power to drive the networking protocols that underpin the IoT.

To read the associated publications please see:

- Assessing the performance of patterned films for diffuse light collection.

- How introducing luminophores affects photopolymerisation.

- Using upconversion to drive a photoswitching reaction.

I also led efforts to implement a ‘living lab’ where a network of internet-enabled lab sensors feed into a monitoring dashboard to easily quantify and assess the environmental impact of scientific research.

Photochemistry at the smallest scales

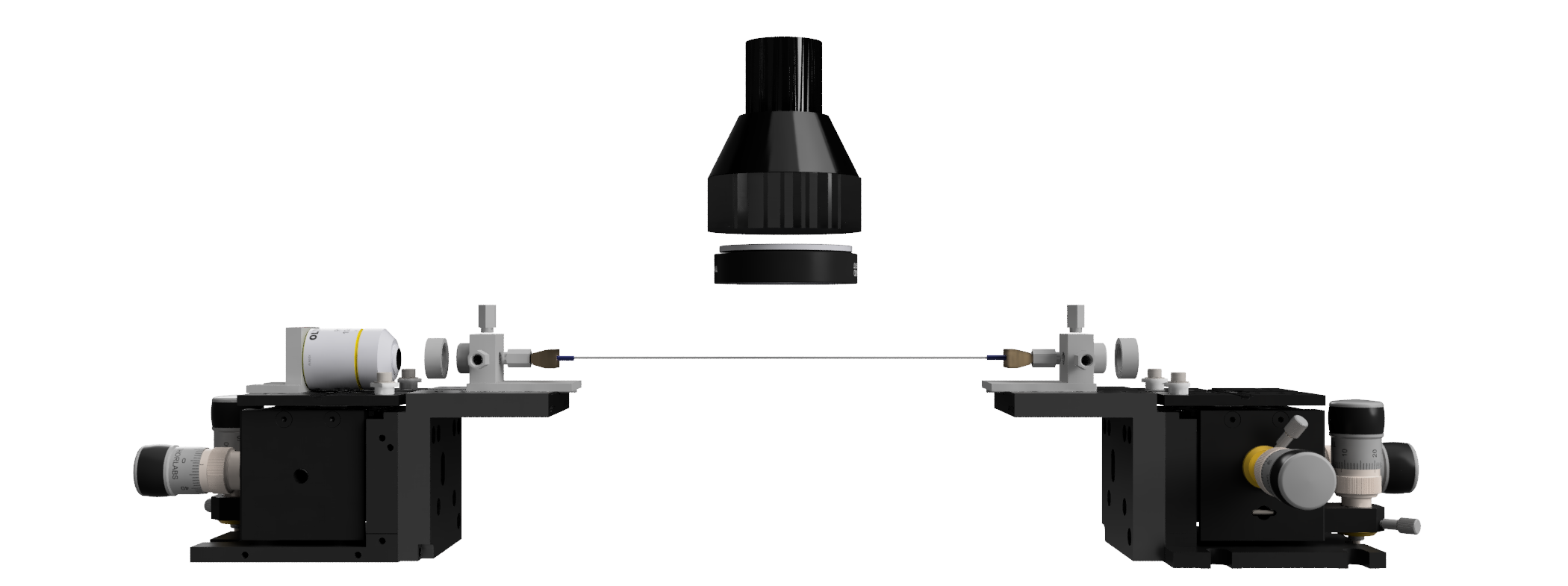

Durng my PhD (Sep 2018 - Aug 2021), I developed a reaction monitoring technology to track photochemical reactions on ~100 nanolitre volumes. I built optofluidic setups for UV-Vis absorbance and fluorescence spectroscopy, generating new kinetic and mechanistic insights into the performance of carbon dots (a light absorber) and cobaloximes (a hydrogen evolution catalyst). During my PhD, I became highly skilled in Python for data wrangling and analysis, and gained proficiency in DFT computational calculations (Gaussian 16) for predicting UV-Vis absorbance and Raman spectra based on molecular structures. I was funded through the NanoDTC.

The Challenge

One method to create hydrogen cleanly is to split up the water molecule (H2O) into hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) using sunlight, just like a leaf on a plant. We can use special chemicals called photocatalysts to do this, which capture energy from sunlight to drive chemical reactions. The problem is no one really knows how these photocatalysts work!

My project seeked to change this by using optical fibres, the same technology that gives us high-speed internet. Optical fibres are glass tubes around the diameter of a human hair, that guide light effectively. The fibres used in my research were hollow in the middle, so a liquid sample could be injected in. Light could be shone down one end of the fibre, and I observed how the light changed as it interacted with the liquid sample. Specifically, chemicals interact with light in different ways, absorbing and emitting specific colours. These ‘spectroscopic signatures’ can be used to work out how the chemicals change and transform with time. The advantage of using optical fibres is the enhanced light-matter interaction over conventional chemical reactors, and the ultralow volumes mean I can minimise usage of expensive and precious samples.

To read the associated publications please see:

- Probing the electron transfer timescales of carbon dot light absorbers.

- Assessing the performance of carbon dot light absorbers.

- Real-time detection of cobaloxime intermediates for hydrogen evolution.

- Quantifying 4CzIPN photocatalyst interactions with other molecules.

- Floating artificial leaves for water splitting.